Caveat: this is a Blink / Chrome view of the world. Most of the main thread tasks are "shared" in some form by all vendors, like layout or style calcs, but this overall architecture may not be.

A picture speaks a thousand words #

It really does, so let's start with one of those:

Processes #

That's a lot of content in a small space, so let's define things a little more. It can be helpful to have the diagram above alongside these definitions, so maybe fire that up image next to this post or, if you're so inclined you could, you know, print it out.

Let's start with the processes:

- Renderer Process. The surrounding container for a tab. It contains multiple threads that, together, are responsible for various aspects of getting your page on screen. These threads are the Compositor, Tile Worker, and Main threads.

- GPU Process. This is the single process that serves all tabs and the surrounding browser process. As frames are committed the GPU process will upload any tiles and other data (like quad vertices and matrices) to the GPU for actually pushing pixels to screen. The GPU Process contains a single thread, called the GPU Thread that actually does the work.

Renderer Process Threads. #

Now let's look at the threads in the Renderer Process.

In many ways you should consider the Compositor Thread as the "big boss". While it doesn't run the JavaScript, Layout, Paint or any of that, it's the thread that is wholly responsible for initiating main thread work, and then shipping frames to screen.

- Compositor Thread. This is the first thread to be informed about the vsync event (which is how the OS tells the browser to make a new frame). It will also receive any input events. The compositor thread will, if it can, avoid going to the main thread and will try and convert input (like - say - scroll flings) to movement on screen. It will do this by updating layer positions and committing frames via the GPU Thread to the GPU directly. If it can't do that because of input event handlers, or other visual work, then the Main thread will be required.

- Main Thread. This is where the browser executes the tasks we all know and love: JavaScript, styles, layout and paint. (That will change in the future under Houdini, where we will be able to run some code in the Compositor Thread.) This thread wins the award for "most likely to cause jank", largely because of the fact that so much runs here.

- Compositor Tile Worker(s). One or more workers that are spawned by the Compositor Thread to handle the Rasterization tasks. We'll talk about that a bit more in a moment.

In many ways you should consider the Compositor Thread as the "big boss". While it doesn't run the JavaScript, Layout, Paint or any of that, it's the thread that is wholly responsible for initiating main thread work, and then shipping frames to screen. If it doesn't have to wait on input event handlers, it can ship frames while waiting for the Main thread to complete its work.

You can also imagine Service Workers and Web Workers living in this process, though I'm leaving them out to because it makes things way more complicated.

The flow of things. #

Let's step through the flow, from vsync to pixels, and talk about how things work out in the "full-fat" version of events. It's worth remembering that a browser need not execute all of these steps, depending on what's necessary. For example, if there's no new HTML to parse, then Parse HTML won't fire. In fact, oftentimes the best way to improve performance is simply to remove the need for parts of the flow to be fired!

oftentimes the best way to improve performance is simply to remove the need for parts of the flow to be fired!

It's also worth noting those red arrows just under styles and layout that seem to point towards requestAnimationFrame. It's perfectly possible to trigger both by accident in your code. This is called Forced Synchronous Layout (or Styles, depending), and it's often bad for performance.

- Frame Start. Vsync is fired, a frame starts.

- Input event handlers. Input data is passed from the compositor thread to any input event handlers on the main thread. All input event handlers (

touchmove,scroll,click) should fire first, once per frame, but that's not necessarily the case; a scheduler makes best-effort attempts, the success of which varies between Operating Systems. There's also some latency between the user interaction and the event making its way to the main thread to be handled. requestAnimationFrame. This is the ideal place to make visual updates to the screen, since you have fresh input data, and it's as close to vsync as you're going to get. Other visual tasks, like style calculations, are due to come after this task, so it's ideally placed to mutate elements. If you mutate - say - 100 classes, this won't result in 100 style calculations; they will be batched up and handled later. The only caveat is that you don't query any computed styles or layout properties (likeel.style.backgroundImageorel.style.offsetWidth). If you do you'll bring recalc styles, layout, or both, forward, causing forced synchronous layouts or, worse, layout thrashing.- Parse HTML. Any newly added HTML is processed, and DOM elements created. You're likely to see a lot more of this during page load or after operations like

appendChild. - Recalc Styles. Styles are computed for anything that's newly added or mutated. This may be the whole tree, or it can be scoped down, depending on what changed. Changing classes on the body can be far-reaching, for example, but it's worth noting that browsers are already very smart about automatically limiting the scope of style calculations.

- Layout. The calculation of geometric information (where and what size each element has) for every visible element. It's normally done for the entire document, often making the computational cost proportional to the DOM size.

- Update Layer Tree. The process of creating the stacking contexts and depth sorting elements.

- Paint: This is the first of a two part process: painting is the recording of draw calls (fill a rectangle here, write text there) for any elements that are new or have changed visually. The second part is Rasterization (see below), where the draw calls are executed, and textures get filled in. This part is the recording of draw calls, and is typically far faster than rasterization, but both parts are often collectively referred to as "painting".

- Composite: the layer and tile information is calculated and passed back to the compositor thread for it to deal with. This will account for, amongst other things, things like

will-change, overlapping elements, and any hardware accelerated canvases. - Raster Scheduled and Rasterize: The draw calls recorded in the Paint task are now executed. This is done in Compositor Tile Workers, the number of which depends on the platform and device capabilities. For example, on Android you typically find one worker, on desktop you can sometimes find four. The rasterization is done in terms of layers, each of which is made up of tiles.

- Frame End: With the tiles for the various layers all rasterized, any new tiles are committed, along with input data (which may have been changed in the event handlers), to the GPU Thread.

- Frame Ships: Last, but by no means least, the tiles are uploaded to the GPU by the GPU Thread. The GPU, using quads and matrices (all the usual GL goodness) will draw the tiles to the screen.

Bonus round #

- requestIdleCallback: if there's any time Main Thread left at the end of a frame then

requestIdleCallbackcan fire. This is a great opportunity to do non-essential work, like beaconing analytics data. If you're new torequestIdleCallbackhave a primer for it on Google Developers that gives a bit more of a breakdown.

Layers and layers #

There are two versions of depth sorting that crop up in the workflow.

Firstly, there's the Stacking Contexts, like if you have two absolutely positioned divs that overlap. Update Layer Tree is the part of the process that ensures that z-index and the like is handled.

Secondly, there's the Compositor Layers, which is later in the process, and applies more to the idea of painted elements. An element can be promoted to a Compositor Layer with the null transform hack, or will-change: transform, which can then be transformed around the place cheaply (good for animation!). But the browser may also have to create additional Compositor Layers to preserve the depth order specified by z-index and the like if there are overlapping elements. Fun stuff!

Riffing on a theme #

Virtually all of the process outlined above is done on the CPU. Only the last part, where tiles are uploaded and moved, is done on the GPU.

On Android, however, the pixel flow is a little different when it comes to Rasterization: the GPU is used far more. Instead of Compositor Tile Workers doing the rasterization, the draw calls are executed as GL commands on the GPU in shaders.

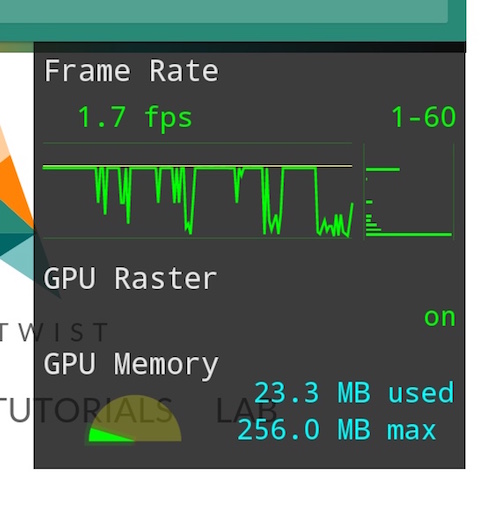

This is known as GPU Rasterization, and it's one way to reduce the cost of paint. You can find out if your page is GPU rasterized by enabling the FPS Meter in Chrome DevTools:

Other resources #

There's a ton of other stuff that you might want to dive into, like how to avoid work on the Main Thread, or how this stuff works at a deeper level. Hopefully these will help you out:

- Compositing in Blink & WebKit. A little old now, but still worth a watch.

- Browser Rendering Performance - Google Developers

- Browser Rendering Performance - Udacity Course (totally free!).

- Houdini - The future, where you get to add more script to more parts of the flow.